By Eric Lee-Mäder, Pollinator Conservation Co-Director of The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

Without much fanfare, a sort of low key nature farming revolution has been taking place in recent years. Among the vast, dusty industrial farmlands of California and the Great Plains, a handful of locals are working to restore native wildflower meadows and long, expansive flowering hedgerows. The goal of this work is to do something that most farmers have never previously thought about doing: to increase the number of insects on their farms.

While much of agriculture still follows a chemical-industrial production model, more and more farmers are awakening to the idea that insects are just as essential to crop production as soil, water, and sunlight. This is especially obvious when we consider the role of pollinators, such as bees. These humble animals not only contribute to the production of crops as diverse as avocados, almonds, apples, canola, chocolate, coffee, and pumpkins, but are also responsible for pollinating a huge range of things we typically feed to livestock, such as alfalfa and clover. Based on current estimates, pollinators – such as bees – are responsible for about 1 out of every 3 bites of food or drink that we consume.

While much of agriculture still follows a chemical-industrial production model, more and more farmers are awakening to the idea that insects are just as essential to crop production as soil, water, and sunlight. This is especially obvious when we consider the role of pollinators, such as bees. These humble animals not only contribute to the production of crops as diverse as avocados, almonds, apples, canola, chocolate, coffee, and pumpkins, but are also responsible for pollinating a huge range of things we typically feed to livestock, such as alfalfa and clover. Based on current estimates, pollinators – such as bees – are responsible for about 1 out of every 3 bites of food or drink that we consume.

Beyond just bees however, there is now a tremendous amount of research demonstrating how much value other beneficial insects provide. ‘Good bugs’ provide natural pest suppression, they create and maintain healthy soils, and even feed on weed seeds. In fact, based upon the best available science, less than 2% of all insect species on Earth are pests, while the overwhelming majority are highly beneficial.

It turns out that the key to increasing beneficial insect numbers on farms is to restore native plant habitat, especially wildflower rich habitat. In a number of key studies, farms that reduce pesticide use and have some natural habitat (typically about 20% of their land base), can often get all their pollination needs from wild, un-managed bees, and much of their pest suppression from other wild beneficial insects. To put it more simply, natural areas export good bugs to nearby crops.

To support this work, the Xerces Society and a number of forward thinking food brands such as Cascadian Farm and Muir Glen have invested nearly eight years of research to design, develop, and field-test optimal habitat systems for these good bugs. Taking advantage of unused land around fencelines and property boundaries, we have restored long linear hedgerows (in some cases thousands of feet in length) consisting of native drought-tolerant flowering shrubs. In other cases, we’ve sown native wildflower meadows on the edges of crop fields. Occasionally we even work directly within the crop, planting flowering cover crops in the understory of almond orchards, for example.

The result of these efforts is beautiful. Often these farm edges explode with color and buzz with insect and songbird activity. They are also functional. In fact, all of the early efforts were backed up by ongoing monitoring of insect populations allowing the farmers to see the real-world impact on beneficial insect populations. Typically those results are dramatic, with a doubling and sometimes a tripling of pollinator numbers with a year of planting these habitats. And the evidence clearly shows that these habitat areas are not favored by pests, and do not increase their numbers at all.

This farming model could not come at a more important time. As promising as these developments are, there is still much work to be done. For example, of our 46 species of wild bumble bees, we believe that 25% of them are now directly at risk of extinction. Monarch butterflies, another iconic and formerly common North American insect have declined by about 90% over the past 20 years. The picture globally is even more stark. Scientists in Germany last year published insect survey results from nature reserves in Western Europe over the past 20 years, showing a 76% decline in insect numbers. When insects cannot survive in nature reserves, the situation is clearly a bad one.

Fortunately there are things that every single person can do. The primary factors impacting beneficial insects such as loss of habitat, and pesticide use can be tackled in our own gardens, communities, and public greenspaces. Planting native plants, especially native wildflowers is correctly promoted as one of the most important steps we can all take. And, once we plant those wildflowers, we need to work tirelessly to protect them from pesticides. We can also take a stand for food systems that work to restore nature. Maybe the solution to agriculture really is as easy as just adding more bees.

The Greatness of Bees

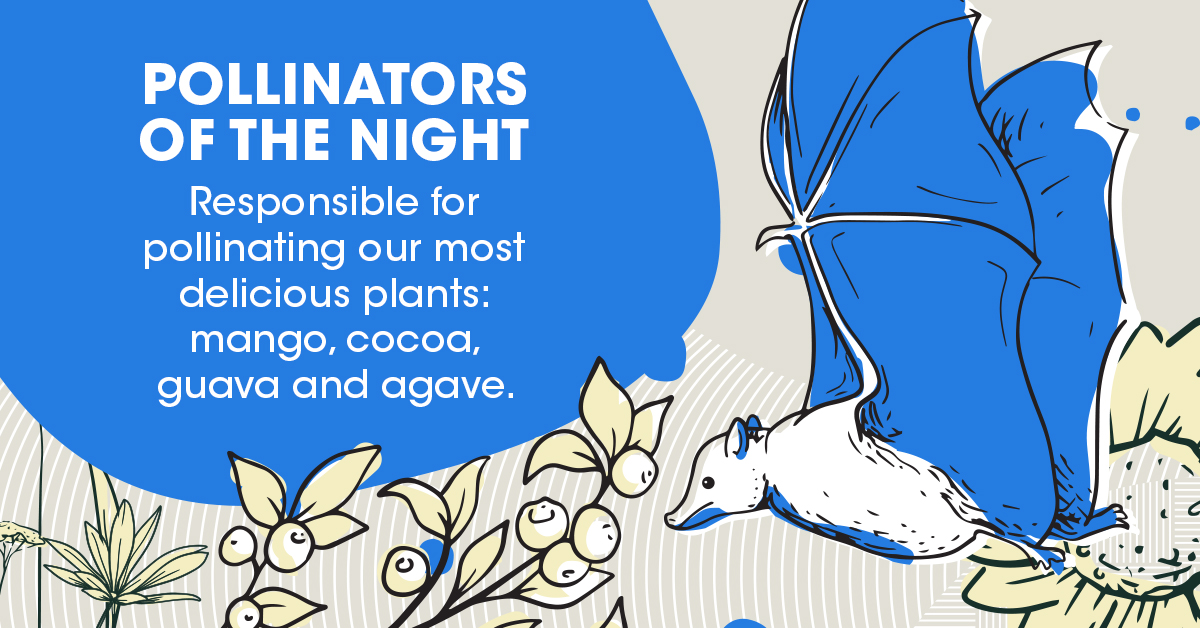

According the best available science, at least 85% of all plant species on Earth either require or strongly benefit from animal pollinators to help them reproduce. These small but mighty creatures move pollen grains between flowers, the first step in sexual reproduction process of plants. The diversity of pollinators is amazing and includes various butterflies, moths, flies, beetles, wasps, bats, hummingbirds, lemurs, and many creatures large and small.

Of the various groups of pollinators, the world’s approximately 20,000 species of bees are considered to be especially important. Unlike most other animals that simply visit flowers for a sugary nectar snack, bees actively collect pollen which they feed to their young. In the process of gathering millions of pollen grains, they inevitably spill some along the way, spreading it between flowers.

This simple act of spilling pollen is both practical and profitable for humans – contributing billions of dollars a year to the food economy – and essential – sustaining plants that produce oxygen, cool the planet, and provide habitat for countless other animal species.

While honey bees historically have gotten all of the attention, they are not native to North America, and are not always the most effective pollinator. In the United States, roughly 4,000 species of wild bees have been identified ranging from tiny bees roughly the size of the letters on this page, to enormous cactus-dwelling carpenter bees that are almost the size of a mouse. These diverse, gentle, and often beautiful bees can be decorated in brilliant metallic blue, green, and purple colors, and have wildly different approaches to nesting, reproduction, and pollen collecting. These wild native bees are among the most important for the pollination of crops such as blueberries, cranberries, pumpkins, avocados, tomatoes, and coffee. Next time you’re in a garden or near a patch of wildflowers, take a close look, say hello, and appreciate what these unsung heroes do for us.